|

Optimization of seam

annealing process

with the help of 2D simulations

John Inge Asperheim and

Leif Markegård

EFD Induction a.s |

Introduction

In the production of welded pipes

according to API standards, a normalization of the weld and heat

affected zone (HAZ) is required. The weld of thick-walled tubes shows an

hour-glass shaped HAZ caused by the ”corner effect” in the weld Vee. The

microstructure, particularly at the external and internal surfaces, is

very coarse-grained. The aim for the heat treatment is to reestablish a

homogeneous and fine-grained microstructure in the HAZ.

To achieve a fine-grained

microstructure after the normalization, it is important to limit the

temperature on the external surface of the pipe, which is closest to the

coil, to avoid grain re-growth, and to reach high enough austenitisation

temperature in a sufficiently wide zone at the inner surface. The width

at the inner surface must cover the width of the HAZ, which has its

maximums at the surfaces, and the positioning tolerance of the heat zone

to the weld.

Even if low frequency is used for the

reheating of the weld zone, the heat penetration through the pipe wall

is partly reliant on heat conduction. Time needed for temperature

equalization through heat conduction increases proportionally to the

square of the wall thickness. The preferred welding method is by

induction, which requires higher minimum welding speed (minimum 10 – 12

m/min) than contact welding (minimum 5 – 6 m/min). One complication with

in-line normalizing heat treatment of thick-walled pipes is that the

heating requires considerable length in a line. This is due to the time

needed for temperature equalization through the pipe wall and the

required line speed. An important design work is to optimize the

temperature distribution in the heat zone and establish the minimum

heating length required. A 2D simulation, using coupled electromagnetic

and transient thermal calculations in a cross-section of the weld as it

passes through the different heating zones, is today an indispensable

tool. It is important to have good representations of the very nonlinear

and temperature dependant electrical and physical properties of the

steel, as well as heat losses by convection and radiation from the

surfaces and residual heat from the welding.

The maximum temperature limit as well

as the required minimum austenitisation temperature is dependent on

actual steel quality and required microstructure. The time at maximum

temperature for the surface close to the coil is from a few seconds up

to a few tens of seconds. Steel used in pipes that are produced

according to API standards normally contains alloy elements that resist

or slow down grain growth. One such element is aluminum, in the form of

fine aluminum nitride particles, that remain un-dissolved up to a

certain temperature. Above this temperature, often referred to as grain

coarsening temperature, the speed of grain growth increases rapidly.

Other alloy elements that slow down grain growth are vanadium, titanium

and niobium [1]. In our calculations we have used 1100ºC as maximum

temperature and 900ºC as required minimum austenitisation temperature.

In a production line the external

surface is accessible for temperature measurements, but the internal

temperature can only be judged through metallurgical examination of the

obtained microstructure (off-line check). The simulation results,

therefore, are also helpful in gaining a view of the temperature

distribution through the pipe wall and taking the right measures in case

of unacceptable results. Normally in a line, the

surface temperature in the center of the heated zone is used to regulate

the power to prevent overheating of the steel.

Normalization is defined as heating

to austenitisation temperature and cooling in still air. This is not the

case for seam normalizing as the colder part of the pipe acts as a

heat-sink and the temperature slope after heating is, first of all, a

result of the internal heat conduction in the pipe. The rather fast

cooling obtained, however, can be beneficial in producing a fine-grained

microstructure. To limit the length of the line one wants to start the

final water-cooling as early as possible. It is, however, important that

the transformation of the austenite be finalized. If the austenite is

retained at the point of water cooling, it results in quenched

microstructure as martensite. This normally is not allowed, at least not

as un-tempered martensite. The ITT (Iso-Temperature-Transformation) and

CCT (Constant-Cooling-Transformation) diagrams of the materials in

question and the calculated cooling curve are helpful tools in designing

the cooling part of the process.

The Model

We have represented the

process by a 2D cross-section of the tube and coil. In the real process

the tube moves through the production line and passes underneath a row

of seam annealing coils. By turning the power on and off it is possible

to simulate this movement. In order to reduce the number of computations

in sequence, we have left out the space between the coils in the study

on coil design. We have, therefore, computed on 3 equivalent sections

and the final cooling after the seam annealing section. The symmetry of

the geometry allows us to model only half the problem. We have used the

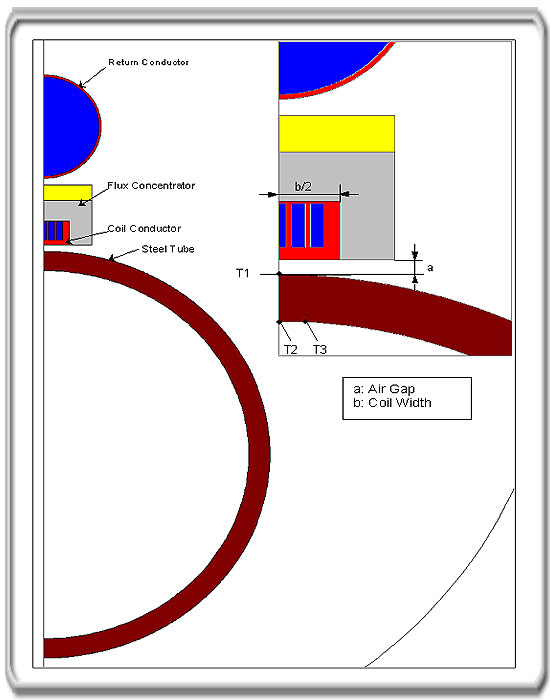

software Flux 2D. The layout of the model with a classical seam

annealing coil is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Computation domain

In the computations only

the tube itself and the surface regions that enable heat exchange from

the tube to the surroundings are included in the thermal part of the

problem. For the regions not included in the thermal part, the

representations of the material properties are simpler. Except for the

magnetic properties of the coil core, they are all constant. The

property assigned to the tube is the same throughout the computations,

but properties for the tube surface can be changed to represent

different cooling conditions.

When the tube arrives at

the first annealing coil, there is a temperature distribution in the

tube wall from the welding process that depends on the speed of the

line, the distance from welder to the first annealing and often water

cooling applied to allow ultrasonic inspection of the weld. The high

temperatures from the welding process are limited to a rather small mass

and even out quite fast [2]. Just as important is the heat generated in

the tube by the current going around the tube underneath the induction

welding coil. In the calculations on coil design presented in this

paper, we have started the computations with an elevated temperature of

200 °C in the entire tube. This temperature is calculated on the basis

of data we have from welders in mills running similar sized tubes.

In the presentation of

the results, we have used three reference points for temperature

measurement. These can be seen in figure 1. Temperatures T1 and T2 are

at the symmetry line in the centre of the tube, T1 on the outer surface

and T2 on the inner surface. The point for temperature measurement T3 is

on the inner surface 10 mm from the symmetry axis.

Measurements

To verify that our

computations are reliable, we have taken some measurements with our

profiled coil. In this test we split one tube along its length to get

two half pipes. This made the inner surface of the tube more accessible

for temperature measurements. A setup like this is slightly different

from an actual mill. Computations, therefore, have been done on the same

“half pipe” setup. We have used material property data for steel 35CD4

(35CrMo4, AISI 4135) because good data is available for this particular

steel and the steel used in the tests, FeE 255, has properties close to

35CD4.

There were several

factors influencing the accuracy of the measurements in this test. Due

to the thermal expansion in the heated zone, the tube will bend when it

is heated. Since we used halves of a tube, the tube’s rigidity was

severely weakened. This allowed the tube to bend much more than it would

in an actual mill and resulted in some movement of the tube during

heating and, therefore, inaccuracy in the position of the thermocouples.

Temperature measurements were taken on a cross-section at the middle

point of the coil. When the tube was heated, we allowed it to bend away

from the coil at the ends. At the same time we placed insulating

material between coil and tube at the mid point to ensure that the

distance between the two remained acceptably constant at this point.

Temperatures are

measured with thermocouples, type K, welded on the inner and outer

surface at distances from the centerline of the tube’s heated zone. The

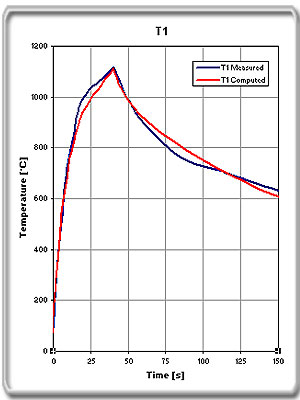

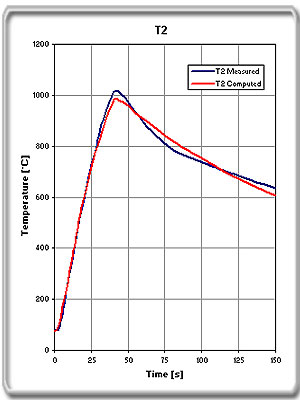

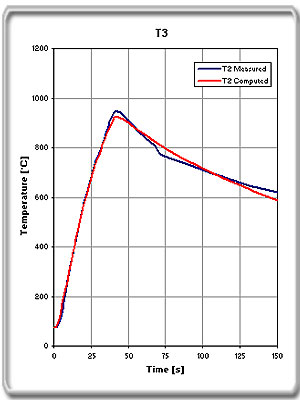

three points representing the temperatures from the computations (T1 –

T3) are presented in figure 2.

|

Figure

2a. T1 |

|

The tube had a

temperature of 75 °C at power on. The computation for direct

comparison with the measurements was started at the same

temperature.

When we compare calculated and measured temperatures, we see

that the measured values are generally a few degrees higher.

This can be explained as inaccuracy in current measurement or

air gap.

Data:

OD Tube: 327 mm

Wall Thickness: 17 mm

Air Gap: 6 mm

Coil Current: 9700 A

Frequency: 1450 Hz |

|

|

Figure

2b. T2 |

Figure

2c. T3 |

|

|

|

|

|

The tube had a

temperature of 75 °C at power on. The computation for direct comparison

with the measurements was started at the same temperature.

When we compare

calculated and measured temperatures, we see that the measured values

are generally a few degrees higher. This can be explained as inaccuracy

in current measurement or air gap.

Data:

OD Tube: 327 mm

Wall Thickness: 17 mm

Air Gap: 6 mm

Coil Current: 9700 A

Frequency: 1450 Hz

The specific heat value v.s. temperature have during

heating a hunch around 730 – 800 °C due to the energy required to

transform the material to austenite. In our calculation, the same

specific heat value v.s. temperature is

used during cooling. In reality the transformation energy

is released at lower temperatures as the transformation from austenite

takes place at lower and cooling-rate-dependant temperatures. This

simplification in representation of material properties is visible in

the curves during cooling. For our purposes, we can conclude that there

is good conformity since we are looking at cooling until transformation

is completed. At this point, all the transformation energy is released.

Coil design

When the coil is narrow compared with

the wall thickness, the heated zone has a shape that resembles a

half-cylinder. The heatflow lines, that are perpendicular to the iso-temperature

lines, bends tangential close to the inner surface. A narrow coil,

therefore, requires longer heating time (zone length) than a wider coil,

where the heatflow has a more radial direction in the required zone

width at the inner surface.

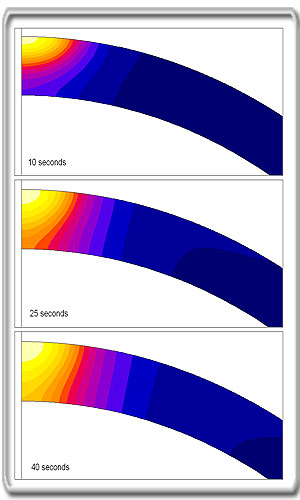

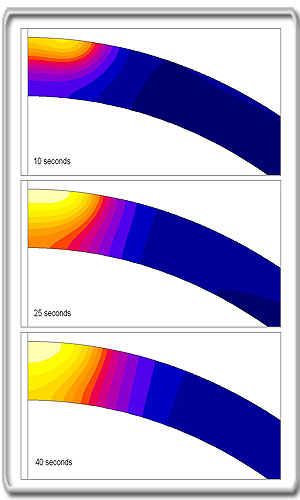

Table 1: Temperature scale for

T-color shade plots

|

|

160 – 220

220 – 280

280 – 340

340 – 400 |

|

400 – 460

460 – 520

520 – 580

580 – 640 |

|

640 – 700

700 – 760

760 – 820

820 – 880 |

|

880 – 940

940 – 1000

1000 –1060

1060 –1120 |

|

Figure 3a. T-colour shade plots

For 45 mm classic coil

|

Figure 3b. T-colour shade plots

For 60 mm EFD Profiled Coil

|

|

|

|

|

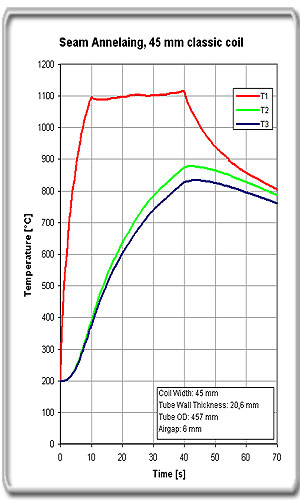

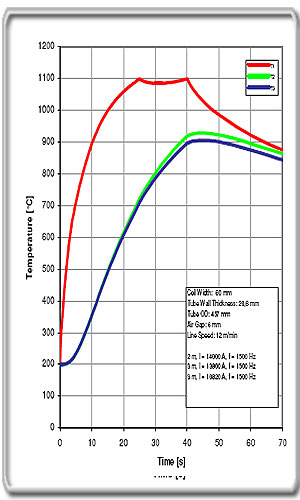

Figure 4a.

Temperature vs. time plots

for 45 mm classic coil |

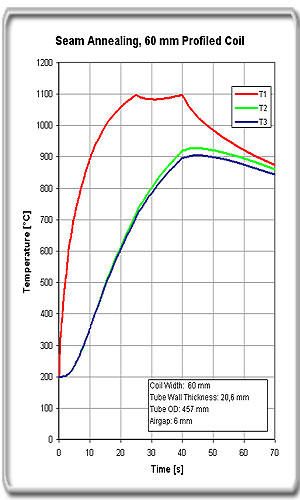

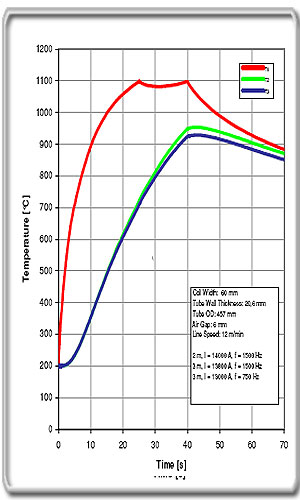

Figure 4b.

Temperature vs. time plots

for 60 mm EFD profiled coil |

When the material passes

Curie-temperature, a non-magnetic ”channel” is formed by the amount of

material that has exceeded the Curie-temperature. The shape of this

”channel”, or zone, determines the current distribution during the time

when this ”channel” is expanding. It is possible to optimize the heated

zone by adapting the coil profile and coil width.

With an increase in the coil width from 45 mm to 60 mm on

wall-thickness 20,6 mm, the required power increases about 14%. The

increase in power is less than the increase in coil width because, for

the wider coil, the zone length can be shorter resulting in a shorter

heating time. With longer heating time, the zone width is widened due to

heat conduction into the pipe.

Normally one type of coil must cover a range of wall

thicknesses. Coils with sufficient width to heat the largest wall

thickness at minimized heating zone length create a wider zone and

require more power than necessary for the smaller wall thickness range.

A wider heated zone gives better temperature homogeneity, which may also

lower the maximum temperature for smaller wall thicknesses. The zone

width also influences the temperature curve’s slope during cooling down

after the heating.

Frequency

We have made a comparison where the two first heating

zones of 2 m and 3 m are run at equal conditions in both cases at a

frequency of 1,5 kHz. In the first case the third zone has a frequency

of 1,5 kHz and in the second case 0,75 kHz. We see that the temperature

difference ∆T = T1 –T3 drops from 193 °C in the first case to 169 °C in

the second case. The conclusion is as expected, a lower frequency

improves the temperature homogeneity. A lower frequency, therefore,

makes it possible to get more power into the tube without exceeding the

maximum temperature at the surface. Another aspect of lowering the

frequency is that the coil impedance will be lower.

|

|

|

Figure. 5a. 3*1500 Hz |

Figure

5b. 2*1500 Hz +1*750 Hz |

|

Conclusions

Comparison of the measurements and calculated results by using Flux2D

shows good conformity. However, we see that our model, using the same

values for specific heat during heating and cooling, gives small errors

in a certain temperature range during cooling.

Shortening the heating zone to a minimum requires optimization of coil

width and profile with respect to wall thickness and speed. However,

optimization of a coil for the most critical wall thickness may have the

consequence that the required power increases for smaller wall

thicknesses due to a zone that is wider than necessary. A wider zone

improves temperature homogeneity and influences on the cooling slope in

the natural cooling zone.

A

lower frequency in the last section improves temperature homogeneity in

the tube. In the frequency range used for this application, acoustic

noise is a problem that has to be addressed.

A 2D

simulation applying coupled electromagnetic and transient thermal

calculations is a very capable and necessary tool for optimization of

the heating and cooling zones of a seam annealing line.

References:

-

Georg Krauss. Steels: Heat Treatment and

Processing Principles, ASM International 1989.

-

Bjørnar Grande, John Inge Asperheim.

Factors Influencing Heavy Wall Tube Welding. Tube and Pipe Technology

March/April 2003.

Contact

Details:

Karianne N. Lunde

Sales- and Marketing Co-ordinator

E-mail:

EFD Induction a.s

P.O. Box 363

N-3701 Skien, Norway

Tel: +47 35 50 60 00

Fax: +47 35 50 60 10

Web:

ww.efd-induction.com

|